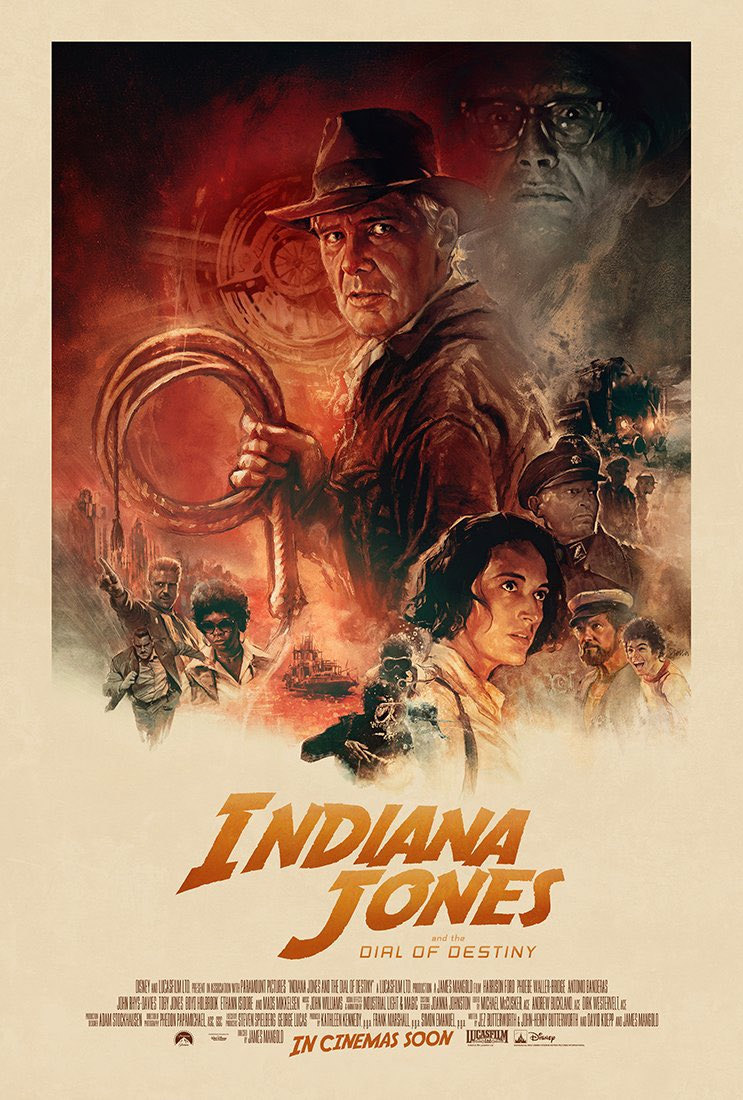

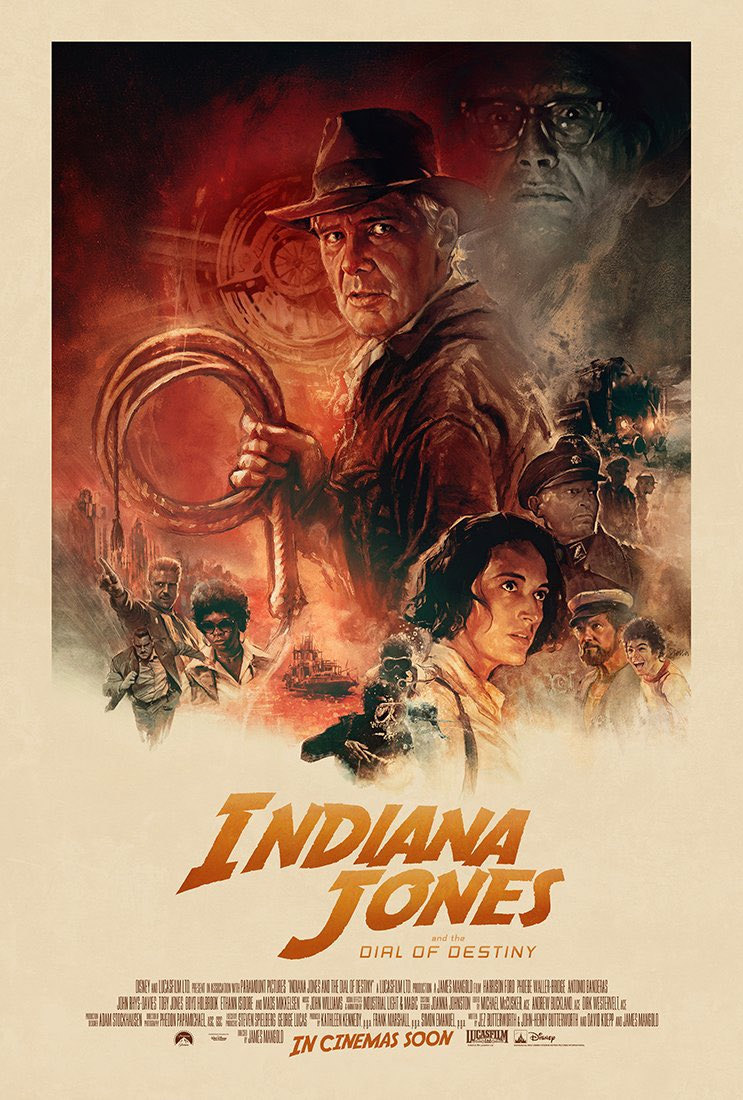

New York, 1969. Archaeologist and occasional tomb raider Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) is about to retire. He’s not quite able to deal with modern society in all its loudness and futurism, as men are now landing on the moon. The past has meant more to him and he’s in mourning for the life he used to have. An adventure is not on his mind, but his god-daughter Helena (Phoebe Waller-Bridge) turns up to rope him into solving the missing piece of his career: the search for the other piece of the Dial of Archimedes, which is said to have mystical properties. They’re not the only ones looking for it. Former Nazi Voller (Mads Mikkelsen) is on Indy and Helena’s trail and has his own arch plans.

We caught up with director James Mangold to find out about bringing the iconic Indiana Jones back to the big screen…

How do you keep the essence of the earlier films but add freshness?

The greatest challenge when I came on board was to figure out a story to tell that had relevance to today and had relevance to a story about Indiana Jones in his 70s, a story that dealt honestly with his age and didn’t pretend he was 40 while he was approaching 80. We all want to live in our youth forever, but even in a fantasy-like life like Indiana Jones, there is a certain measure of reality, and the reality is our actor looks different than he used to. Just because I could replace him with a stuntman every time he jumps doesn’t mean that the movie necessarily is better, it just becomes less honest about where this character would be at this stage of his life. The challenge was coming up with a notion of the relic they’d be chasing and the theme of the whole show, which, for me, was about time, as in ageing. Our ageing, all of us, even heroes, and the time as in how the world changes around us. The time also as an archaeologist, in that Indy is always focused on what’s behind him and its relevance to what’s in front of him.

You worked with Harrison Ford as a producer on Call of the Wild. What was it like working with him as a director?

Working with Harrison was a thrill of a lifetime. We’ve been friends for a while. I worked with him as a producer on a previous film and had gotten quite close to him. He’s one of our icons and legends on the screen, but he’s also such a unique actor. People say movie star, some say actor; I would rather refer to him, despite his supreme status as a movie star, as an actor because the process of working with him is not the process of working with a star. He doesn’t ask how do I look? or want the best lines or all the heroic moments. Harrison is always digging and scratching for the humanity of his character. The appeal of Indiana Jones movies and Harrison’s work, in general, is built upon not only his good looks and his charm but the fact that he loves to explore the foibles and eccentricities and even flaws of his characters. Even when his characters are in a heroic or leading man position, he’s not afraid to allow the audience in and make a hero more like you or me and that includes his really deft comic timing and touches, which are so much a part of his portrayal of Indy and the charm of these movies.

Indy’s old foes, the Nazis, are back. What made you decide to keep the continuity of the Nazis as villains?

There are some things within the story universe that are constant. The battle against ignorance, bigotry, lies, and fascism is constant. What I thought would be interesting about it was to find these Nazis living in a modern world. The first three Indiana Jones films take place in a golden period. Not only of cinema but of world history, in the 30s and 40s when our own sense of purpose and right and wrong was so crystal clear. It gave juice to those original films in tone and in style. They were in the style of the Golden Age film, John Williams was scoring in the style of a Golden Age film, our hero was wearing a fedora and carrying a revolver, and there was a sense from top to bottom of thematic and stylistic unity, in tribute to the Golden Age films that I think Steven and George are so inspired by. The challenge in the fourth film and certainly for me in the fifth film is that Indiana Jones now takes place in a period of modernism, both in Crystal Skull [1950s] and in this film [1960s]. There is no longer this easy unity between the stylization of the movie and the time period it takes place. The world is not so clear about good and bad anymore; the enemy of my enemy is my friend. The world is not so clearly looking to uncover the secrets of its past but much more looking forward toward its future in space, nuclear power, and the new realities of life. Youth culture and the moment culturally, in general, is not one about the previous generations but much more a rejection of what’s been done by the generations that preceded them. In so many ways, the element of the Nazis in the movie, while a constant, was a new concept of the Nazis, which is how they’ve infiltrated Western life and how they become a part of our own Western life. In the case of Boyd Holbrook’s character, you have a southern American boy, who’s pledging allegiance to the Nazis, and that, to me, was a reflection not merely of the current times but of modern times in which these same strokes, the same movements, the same forces now occupy new and less obvious positions in our world. It’s less easy to identify them so quickly.

This is not your first final chapter film. You brought Wolverine’s story to a close in Logan. What makes your approach to each swansong different from a directorial point of view?

My inspiration for Logan was to make a harder comic book movie that reflected contemporary times as well as we could at the moment, but one that also took a hero who was virtually indestructible and found a vulnerability in him. It’s actually very hard to make a movie about an indestructible character because it means that they have nothing at stake in the movie. They can’t be hurt. But what’s so interesting about Logan is, of course, he can hurt; his whole life has been painful. In a sense, he is an extension of the Frankenstein monster, a creation of both nature and man in a collaboration that has made him a walking weapon. How do you come to peace with that? These are all questions of Logan. Indiana Jones also finds another hero in the twilight years, but it is an entirely different tone. Indiana Jones and his films are humorous. They’re jaunty, unlike a lot of action-adventure movies now. The action in Indiana Jones films is not so brutalist; it is more playful. The action becomes almost a musical number and very often features comedic touches. As Steven staged them in the past, and certainly I tried to, it was as much inspired by Buster Keaton as it is by James Bond. The difference is that Keaton always played a frail human, overwhelmed by his opposition, who was stalwart and never quit but sometimes survived out of sheer luck. A very big part of what makes Indiana Jones films charming is that they exist in this nexus of character work and action, in which your hero is not an unstoppable shield against all harm but is quite vulnerable.

Words – Cara O’Doherty

INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY is at Irish cinemas from June 28th