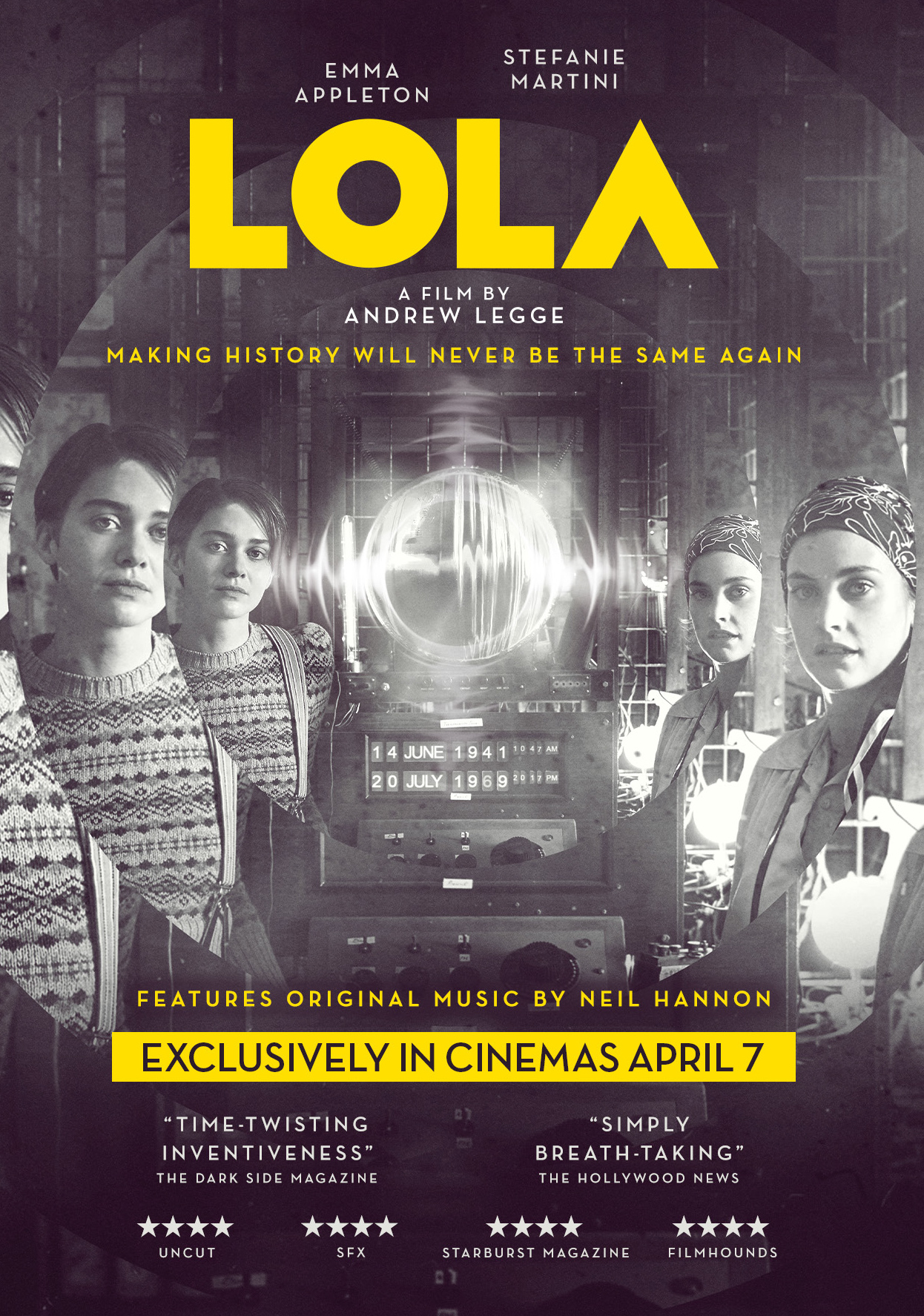

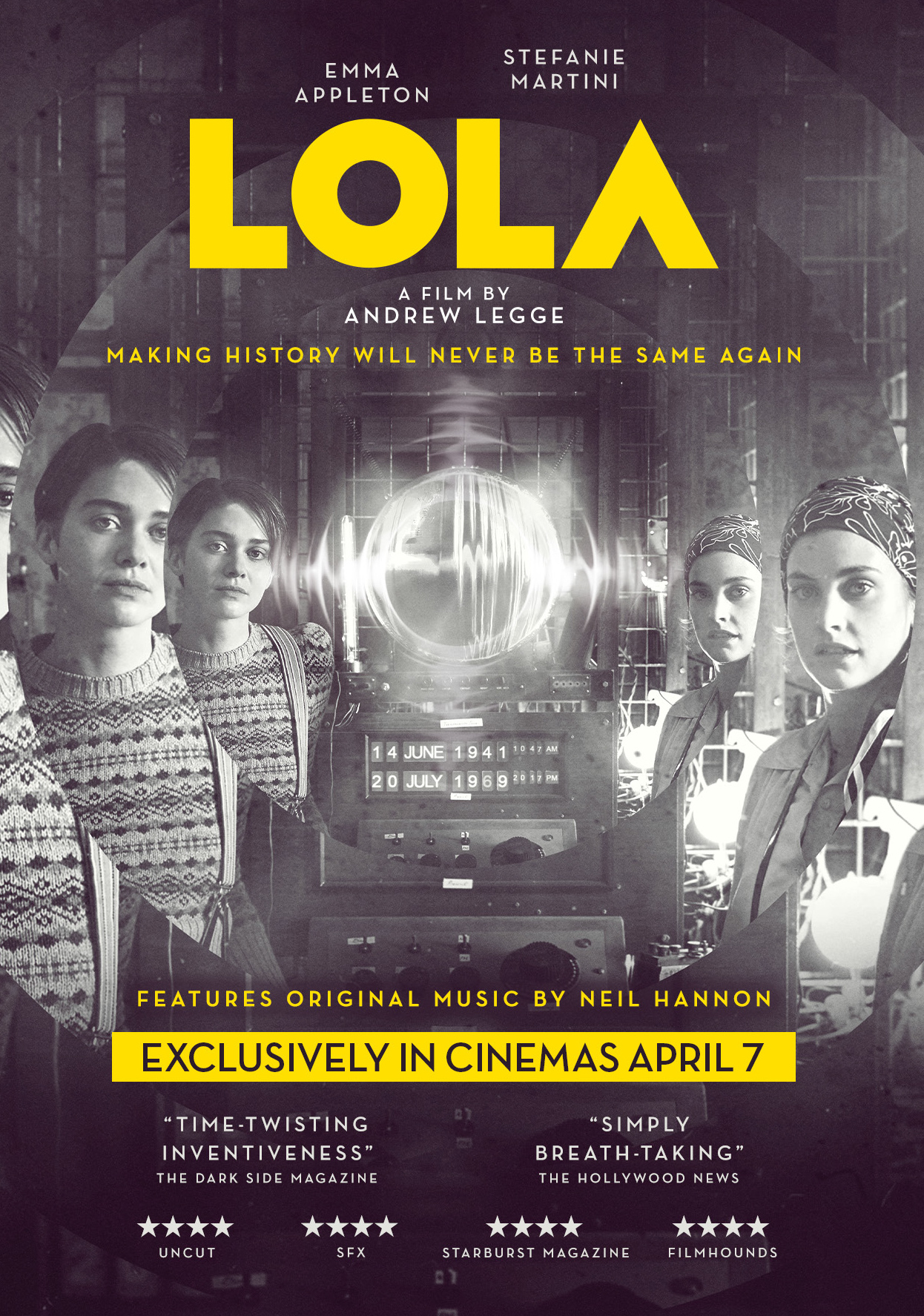

Writer-director Andrew Legge takes an inventive look at the 1940s in Lola, which follows two sisters, Thomasina (Emma Appleton) and Martha (Stefanie Martini), who build a unique machine. Named Lola, the machine can broadcast news stories from the future. At first, the sisters are wrapped up in a new world of 1970s music and dance, but soon they realise Lola isn’t just a tool for fun. They decide to use Lola to change the course of the war and help defeat the Nazis, but messing with time can have unforeseen consequences. Legge tells about bringing Lola to life and shooting in black and white.

Lola is unlike anything I have seen in a long time; where did the concept come from?

I made a short film that was similar but was more like a traditional pseudo-documentary about a scientist who could see into the past. I always had the idea of expanding that into a feature partly because I wanted to do something high concept and sci-fi with my first film, but I knew it was going to be on a limited budget because it was my first feature. I wanted to try high-concept sci-fi, but because of my low budget, I knew that shooting in black and white with Bolex cameras would make it much more affordable. It gives you a lot more control in terms of not needing a huge crew, it looks very authentic when it comes out of the camera, and it makes shooting more mobile.

I looked at the idea of going into the past, but it was more interesting to have characters who could see into the future and what that would mean if you could access information. What would you do if you thought you could change the future?

Then the music aspect came into it, you have these characters living in the 1940s just before the whole explosion of pop culture that would happen in the 1550s and 1960s. What would it mean for these women who were getting culture from another era, an era that wasn’t their own? It was exciting to me to use the machine as a way of bringing a different culture to the past.

Neil Hannan wrote the music for the film. How did he come on board?

My producer, Alan Maher, suggested that Neil Hannon do the music, which was a really great idea because he has the ability to bring styles of music together. We have a soundtrack with typical 40s music played on 40s instruments but inspired by the type of music they might have heard on Lola from the future. Neil wrote some of the music before we started shooting so we would have it for playback while we were filming, and he did the rest when we were in post. It was an amazing strike of luck to get him; his work really elevates the film.

The film is shot in black and white on 16 and 35mm, some of it on Bolex cameras, as you mentioned before. The actors shot much of the footage themselves, but how did that work, and did you train them to use the cameras?

We used period cameras for all of it, and it was all shot on film. All of Martha’s stuff was shot on 16mm, and then we shot the newsreels on 35mm because that’s how they would have been shot at the time. We used the 35mm newsreel camera from the 1930s called a Newman Sinclair, and then we shot a lot of Martha’s footage on the Bolex. We also used another, more modern camera with an older lens. We shot during covid, so the actors had to isolate together before we started shooting; so, we gave the actors the cameras, and they learned how to use them during their time in isolation. As a character, Martha is always filming, so it made sense for Stephanie, the actor who plays her, to film. It worked better for eyelines and made the footage more believable. Because we were shooting this on these old cameras, the rushes came back looking pretty much how we wanted them to look.

Archival footage is a considerable part of the film, and some of it is manipulated. What was that process like?

We used archival footage and manipulated it to create an altered future. We changed billboards in London, added slogans or changed slogans, and made small changes to indicate that the future wasn’t as it should be. We needed to use actual footage of Hitler, but again we manipulated archival footage so we could put him where we needed him to be. I spent about three months before we started shooting looking through the archive for stuff that was in the script. I went down some rabbit holes, but sometimes the rabbit hole was really useful. There is a scene with an angry mob, and I found the exact footage I needed by getting lost in some other footage one day. The manipulation and the archival footage will make a lot more sense when people see the film; it is hard to talk about it without giving too much away.

How did you design Lola?

Jack Phelan designed it, and Robert Clark built it. Jack had free rein, but I did give him a brief. Lola had to feel like something that these two women could conceivably build in the 40s. It had to look homemade like it was made from salvaged wirelesses and circuit boards from the 1940s. The other was that Lola had to be big and almost tower over the sisters to add to its personality. The final thing was that Lola needed work; we didn’t want to add anything in post, so Jack got a glassblower to make a glass piece that could be used to reflect images out so when the sisters are watching images from the future on Lola, they are doing it in real-time. I love that we were able to make Lola function, but it did make things more complicated in terms of the projector and queuing up the stuff that needed to play. We also had to factor in the logistics; there are no labs here, so we had to ship the things you see on Lola’s screen to the lab in London. It would take two or three days to get that done.

Your daughters play the sisters in a flashback at the start of the film. What was it like working with them?

It was brilliant. I didn’t shoot them with a crew; I would grab the Bolex at the weekend, do little things with them, and capture it. It was great because they weren’t scared of the camera, and we could shoot whenever we wanted. If you work with kids, the rules are very strict about how long you can shoot for and when you can shoot, but you have freedom with your own kids. I was also lucky that they have hair similar to the older actors and, as sisters, have natural chemistry. In terms of the characters, that footage would have been filmed by one of their parents, so it felt more authentic to have me do it.

Words – Cara O’Doherty

LOLA is at cinemas from April 7th